1852 Speech by African American Leader Frederick Douglass

The following is an abridged version of a speech African American leader Frederick Douglass gave on July 5, 1852, in Rochester, New York. He had been invited to address the Rochester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society on the occasion of the July 4 national holiday.

World-Outlook is publishing it to mark U.S. Independence Day. Though not often presented this way today, July 4, 1776, was a starting moment of one of the world’s first anti-colonial revolutions. But like others that followed, it was marked by both successes and failures. Allowing chattel slavery with all its horrors to flourish was the main manifestation of its decay.

Douglass delivered this famous address at a time when slavery reigned supreme in the U.S. South and the planter aristocracy dominated national politics. Without dismissing the significance for humanity of the first American revolution, Douglass eloquently pointed to the degeneration of that far-reaching anti-colonial struggle and the need for a second American revolution to eradicate slavery.

Nearly 170 years have passed since then. During this time, U.S. society has undergone major transformations through momentous events. These include the U.S. Civil War, the rise and fall of Radical Reconstruction, the subsequent century of Jim Crow segregation, the emergence of the United States as an imperialist power at the dawn of the 20th century, and the mass civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

The ideas Douglass outlined in his 1852 address, however, retain value for today despite the passage of time and the historic events that have transpired during nearly two centuries. They are especially relevant to those involved in current struggles against police brutality and racism. They will be appreciated by those fighting for a world based on human solidarity and social equality rather than the class injustice, dog-eat-dog competition, and bigotry that are prevalent in the United States today.

Douglass was an enslaved Black man who escaped his masters and became a prominent leader in the abolitionist movement, which sought to eradicate slavery before and during the Civil War. After the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 and the end of the Civil War two years later, he continued to push for racial and social equality and for women’s rights until his death in 1895. (A sketch of Frederick Douglass’ life can be found in the introduction to Part I of this series.)

His life and work serve as an inspiration for millions to this day. As the African American leader said, “We have to do with the past only as we can make it useful to the present and to the future.” It’s in this spirit that World-Outlook publishes Douglass’ Fourth of July speech.

The text below is taken from the online edition of Douglass’ speech—now in the public domain—by Mass for Humanities (masshumanities.org)[1]. The full version of the speech is easily accessible here.[2] Subheadings and footnotes are by World-Outlook.com. Due to its length, we are publishing it in three parts, the second of which follows.[3] The first can be found here.

DOCUMENTS

By Frederick Douglass

I shall see, this day, and its popular characteristics, from the slave’s point of view. Standing, there, identified with the American bondman, making his wrongs mine, I do not hesitate to declare, with all my soul, that the character and conduct of this nation never looked blacker to me than on this 4th of July!

Slavery: America’s great shame

Whether we turn to the declarations of the past, or to the professions of the present, the conduct of the nation seems equally hideous and revolting. America is false to the past, false to the present, and solemnly binds herself to be false to the future. Standing with God and the crushed and bleeding slave on this occasion, I will, in the name of humanity, which is outraged, in the name of liberty, which is fettered, in the name of the constitution and the Bible, which are disregarded and trampled upon, dare to call in question and to denounce, with all the emphasis I can command, everything that serves to perpetuate slavery—the great sin and shame of America!

“I will not equivocate; I will not excuse.” I will use the severest language I can command; and yet not one word shall escape me that any man, whose judgment is not blinded by prejudice, or who is not at heart a slaveholder, shall not confess to be right and just.

But I fancy I hear some one of my audience say, it is just in this circumstance that you and your brother abolitionists fail to make a favorable impression on the public mind. Would you argue more, and denounce less, would you persuade more, and rebuke less, your cause would be much more likely to succeed. But I submit, where all is plain there is nothing to be argued. What point in the anti-slavery creed would you have me argue? On what branch of the subject do the people of this country need light? Must I undertake to prove that the slave is a man? That point is conceded already. Nobody doubts it. The slaveholders themselves acknowledge it in the enactment of laws for their government.

They acknowledge it when they punish disobedience on the part of the slave. There are seventy-two crimes in the State of Virginia, which, if committed by a Black man, (no matter how ignorant he be), subject him to the punishment of death, while only two of the same crimes will subject a white man to the like punishment. What is this but the acknowledgement that the slave is a moral, intellectual and responsible being? The manhood of the slave is conceded. It is admitted in the fact that Southern statute books are covered with enactments forbidding, under severe fines and penalties, the teaching of the slave to read or to write. When you can point to any such laws, in reference to the beasts of the field, then I may consent to argue the manhood of the slave. …

For the present, it is enough to affirm the equal manhood of the Negro race. Is it not astonishing that, while we are ploughing, planting and reaping, using all kinds of mechanical tools, erecting houses, constructing bridges, building ships, working in metals of brass, iron, copper, silver and gold; that, while we are reading, writing and cyphering, acting as clerks, merchants and secretaries, having among us lawyers, doctors, ministers, poets, authors, editors, orators and teachers; that, while we are engaged in all manner of enterprises common to other men, digging gold in California, capturing the whale in the Pacific, feeding sheep and cattle on the hill-side, living, moving, acting, thinking, planning, living in families as husbands, wives and children, and, above all, confessing and worshipping the Christian’s God, and looking hopefully for life and immortality beyond the grave, we are called upon to prove that we are men!

Would you have me argue that man is entitled to liberty? That he is the rightful owner of his own body? You have already declared it. Must I argue the wrongfulness of slavery? Is that a question for Republicans? Is it to be settled by the rules of logic and argumentation, as a matter beset with great difficulty, involving a doubtful application of the principle of justice, hard to be understood? …There is not a man beneath the canopy of heaven, that does not know that slavery is wrong for him.

What, am I to argue that it is wrong to make men brutes, to rob them of their liberty, to work them without wages, to keep them ignorant of their relations to their fellow men, to beat them with sticks, to flay their flesh with the lash, to load their limbs with irons, to hunt them with dogs, to sell them at auction, to sunder their families, to knock out their teeth, to bum their flesh, to starve them into obedience and submission to their masters? Must I argue that a system thus marked with blood, and stained with pollution, is wrong? No! I will not. I have better employments for my time and strength than such arguments would imply.

What, then, remains to be argued? Is it that slavery is not divine, that God did not establish it, that our doctors of divinity are mistaken? There is blasphemy in the thought. That which is inhuman, cannot be divine! Who can reason on such a proposition? They that can, may; I cannot. The time for such argument is past.

‘It is not light that is needed, but fire’

At a time like this, scorching irony, not convincing argument, is needed. O! had I the ability, and could I reach the nation’s ear, I would, today, pour out a fiery stream of biting ridicule, blasting reproach, withering sarcasm, and stern rebuke. For it is not light that is needed, but fire; it is not the gentle shower, but thunder. We need the storm, the whirlwind, and the earthquake. The feeling of the nation must be quickened; the conscience of the nation must be roused; the propriety of the nation must be startled; the hypocrisy of the nation must be exposed; and its crimes against God and man must be proclaimed and denounced.

What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? I answer: a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelly to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciations of tyrants, brass fronted impudence; your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings, with all your religious parade, and solemnity, are, to him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy—a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages. There is not a nation on the earth guilty of practices, more shocking and bloody, than are the people of these United States, at this very hour.

Go where you may, search where you will, roam through all the monarchies and despotisms of the old world, travel through South America, search out every abuse, and when you have found the last, lay your facts by the side of the everyday practices of this nation, and you will say with me, that, for revolting barbarity and shameless hypocrisy, America reigns without a rival.

Internal slave trade

Take the American slave trade, which, we are told by the papers, is especially prosperous just now. Ex-Senator Benton tells us that the price of men was never higher than now. He mentions the fact to show that slavery is in no danger. This trade is one of the peculiarities of American institutions. It is carried on in all the large towns and cities in one-half of this confederacy; and millions are pocketed every year, by dealers in this horrid traffic. In several states, this trade is a chief source of wealth. It is called (in contradistinction to the foreign slave-trade) “the internal slave trade.” It is, probably, called so, too, in order to divert from it the horror with which the foreign slave-trade is contemplated.

That trade has long since been denounced by this government, as piracy. It has been denounced with burning words, from the high places of the nation, as an execrable traffic. To arrest it, to put an end to it, this nation keeps a squadron, at immense cost, on the coast of Africa. Everywhere, in this country, it is safe to speak of this foreign slave-trade, as a most inhuman traffic, opposed alike to the laws of God and of man. The duty to extirpate and destroy it, is admitted even by our DOCTORS OF DIVINITY.

In order to put an end to it, some of these last have consented that their colored brethren (nominally free) should leave this country, and establish themselves on the western coast of Africa!

It is, however, a notable fact that, while so much execration is poured out by Americans upon those engaged in the foreign slave-trade, the men engaged in the slave trade between the states pass without condemnation, and their business is deemed honorable.

Behold the practical operation of this internal slave-trade, the American slave-trade, sustained by American politics and America religion. Here you will see men and women reared like swine for the market. You know what is a swine-drover? I will show you a man-drover. They inhabit all our Southern States. They perambulate the country, and crowd the highways of the nation, with droves of human stock. You will see one of these human flesh-jobbers, armed with pistol, whip and bowie-knife, driving a company of a hundred men, women, and children, from the Potomac to the slave market at New Orleans.

These wretched people are to be sold singly, or in lots, to suit purchasers. They are food for the cotton-field, and the deadly sugar-mill. Mark the sad procession, as it moves wearily along, and the inhuman wretch who drives them. Hear his savage yells and his blood-chilling oaths, as he hurries on his affrighted captives! There, see the old man, with locks thinned and gray. Cast one glance, if you please, upon that young mother, whose shoulders are bare to the scorching sun, her briny tears falling on the brow of the babe in her arms. See, too, that girl of thirteen, weeping, yes! weeping, as she thinks of the mother from whom she has been torn! The drove moves tardily. Heat and sorrow have nearly consumed their strength; suddenly you hear a quick snap, like the discharge of a rifle; the fetters clank, and the chain rattles simultaneously; your ears are saluted with a scream, that seems to have torn its way to the center of your soul!

The crack you heard, was the sound of the slave-whip; the scream you heard, was from the woman you saw with the babe. Her speed had faltered under the weight of her child and her chains! that gash on her shoulder tells her to move on. Follow the drove to New Orleans. Attend the auction; see men examined like horses; see the forms of women rudely and brutally exposed to the shocking gaze of American slave-buyers. See this drove sold and separated forever; and never forget the deep, sad sobs that arose from that scattered multitude. Tell me citizens, WHERE, under the sun, you can witness a spectacle more fiendish and shocking. Yet this is but a glance at the American slave-trade, as it exists, at this moment, in the ruling part of the United States.

‘I was born amid such… terrible reality’

I was born amid such sights and scenes. To me the American slave-trade is a terrible reality. When a child, my soul was often pierced with a sense of its horrors. I lived on Philpot Street, Fell’s Point, Baltimore, and have watched from the wharves, the slave ships in the Basin, anchored from the shore, with their cargoes of human flesh, waiting for favorable winds to waft them down the Chesapeake.

There was, at that time, a grand slave mart kept at the head of Pratt Street, by Austin Woldfolk. His agents were sent into every town and county in Maryland, announcing their arrival, through the papers, and on flaming “hand-bills,” headed CASH FOR NEGROES. These men were generally well-dressed men, and very captivating in their manners. Ever ready to drink, to treat, and to gamble. The fate of many a slave has depended upon the turn of a single card; and many a child has been snatched from the arms of its mother by bargains arranged in a state of brutal drunkenness.

The flesh-mongers gather up their victims by dozens, and drive them, chained, to the general depot at Baltimore. When a sufficient number have been collected here, a ship is chartered, for the purpose of conveying the forlorn crew to Mobile, or to New Orleans. From the slave prison to the ship, they are usually driven in the darkness of night; for since the antislavery agitation, a certain caution is observed.

In the deep still darkness of midnight, I have been often aroused by the dead heavy footsteps, and the piteous cries of the chained gangs that passed our door. The anguish of my boyish heart was intense; and I was often consoled, when speaking to my mistress in the morning, to hear her say that the custom was very wicked; that she hated to hear the rattle of the chains, and the heart-rending cries. I was glad to find one who sympathized with me in my horror.

Fellow-citizens, this murderous traffic is, to-day, in active operation in this boasted republic. In the solitude of my spirit, I see clouds of dust raised on the highways of the South; I see the bleeding footsteps; I hear the doleful wail of fettered humanity, on the way to the slave-markets, where the victims are to be sold like horses, sheep, and swine, knocked off to the highest bidder. There I see the tenderest ties ruthlessly broken, to gratify the lust, caprice and rapacity of the buyers and sellers of men. My soul sickens at the sight.

“Is this the land your Fathers loved,

The freedom which they toiled to win?

Is this the earth whereon they moved?

Are these the graves they slumber in?”

But a still more inhuman, disgraceful, and scandalous state of things remains to be presented. By an act of the American Congress, not yet two years old, slavery has been nationalized in its most horrible and revolting form. By that act, Mason & Dixon’s line has been obliterated; New York has become as Virginia; and the power to hold, hunt, and sell men, women, and children as slaves remains no longer a mere state institution, but is now an institution of the whole United States.

The power is co-extensive with the Star-Spangled Banner and American Christianity. Where these go may also go the merciless slave hunter. Where these are, man is not sacred. He is a bird for the sportsman’s gun. By that most foul and fiendish of all human decrees, the liberty and person of every man are put in peril. Your broad republican domain is hunting ground for men. Not for thieves and robbers, enemies of society, merely, but for men guilty of no crime.

Your lawmakers have commanded all good citizens to engage in this hellish sport. Your President, your Secretary of State, your lords, nobles, and ecclesiastics, enforce, as a duty you owe to your free and glorious country, and to your God, that you do this accursed thing. Not fewer than forty Americans have, within the past two years, been hunted down and, without a moment’s warning, hurried away in chains, and consigned to slavery and excruciating torture. Some of these have had wives and children, dependent on them for bread; but of this, no account was made. The right of the hunter to his prey stands superior to the right of marriage, and to all rights in this republic, the rights of God included! For Black men there are neither law, justice, humanity, not religion.

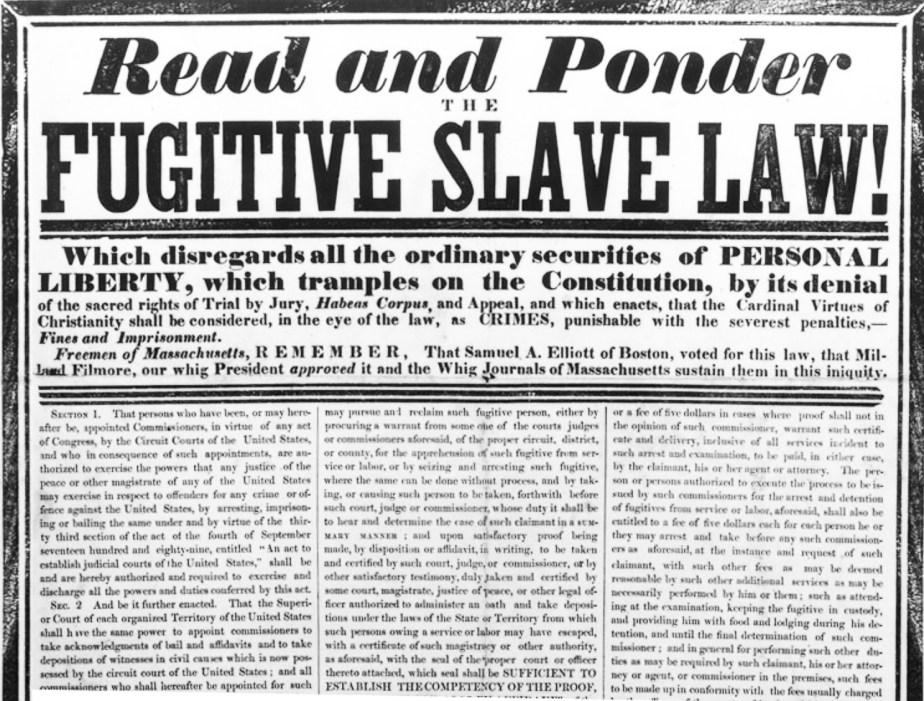

Fugitive Slave Law

The Fugitive Slave Law makes MERCY TO THEM, A CRIME; and bribes the judge who tries them. An American JUDGE GETS TEN DOLLARS FOR EVERY VICTIM HE CONSIGNS to slavery, and five, when he fails to do so. The oath of any two villains is sufficient, under this hell-black enactment, to send the most pious and exemplary Black man into the remorseless jaws of slavery! His own testimony is nothing. He can bring no witnesses for himself. The minister of American justice is bound by the law to hear but one side; and that side, is the side of the oppressor.

Let this damning fact be perpetually told. Let it be thundered around the world, that, in tyrant-killing, king-hating, people-loving, democratic, Christian America, the seats of justice are filled with judges, who hold their offices under an open and palpable bribe, and are bound, in deciding in the case of a man’s liberty, hear only his accusers!

In glaring violation of justice, in shameless disregard of the forms of administering law, in cunning arrangement to entrap the defenseless, and in diabolical intent, this Fugitive Slave Law stands alone in the annals of tyrannical legislation. I doubt if there be another nation on the globe, having the brass and the baseness to put such a law on the statute-book. If any man in this assembly thinks differently from me in this matter, and feels able to disprove my statements, I will gladly confront him at any suitable time and place he may select.

(To be continued)

ENDNOTES

[1] https://masshumanities.org/programs/douglass/

[2] This is one of the sites where Frederick Douglass’ 1852 speech is available in its entirety: https://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/document/what-to-the-slave-is-the-fourth-of-july/

[3] The first part of this series can be found in Part I.

Recommended Books

- Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave by Frederick Douglass

This is a Original Edition which was first Published in 1845. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass is an 1845 memoir and treatise on abolition written by famous orator and former slave Frederick Douglass. It is generally held to be the most famous of a number of narratives written by former slaves during the same period.

Born a slave circa 1818 (slaves weren’t told when they were born) on a plantation in Maryland, Douglass taught himself to read and write. This book calmly but dramatically recounts the horrors and the accomplishments of his early years—the daily, casual brutality of the white masters; his painful efforts to educate himself; his decision to find freedom or die; and his harrowing but successful escape.

An astonishing orator and a skillful writer, Douglass became a newspaper editor, a political activist, and an eloquent spokesperson for the civil rights of African Americans. He lived through the Civil War, the end of slavery, and the beginning of segregation. He was celebrated internationally as the leading black intellectual of his day, and his story still resonates in ours.

A True Classic that Belongs on Every Bookshelf!

- The Fall of the House of Dixie: The Civil War and the Social Revolution That Transformed the South by Bruce Levine

- America’s Revolutionary Heritage by George Novack

Available at: https://www.pathfinderpress.com/products/americas-revolutionary-heritage-marxist-essays_by-george-novack

- Black Reconstruction in America 1860-1880 by W.E.B. DuBois

This pioneering work was the first full-length study of the role Black Americans played in the crucial period after the Civil War, when the slaves had been freed and the attempt was made to reconstruct American society. Hailed at the time, Black Reconstruction in America 1860–1880 has justly been called a classic.

Available at: https://www.amazon.com/Black-Reconstruction-America-1860-1880-Burghardt/dp/0684856573/ref=tmm_pap_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=1623960262&sr=8-3

- The Souls of Black Folk by W.E.B. Dubois

The Souls of Black Folk is a 1903 work of American literature by W. E. B. Du Bois. It is a seminal work in the history of sociology and a cornerstone of African-American literature.

The book contains several essays on race, some of which the magazine Atlantic Monthly had previously published. To develop this work, Du Bois drew from his own experiences as an African American in U.S. society. In particular, DuBois presents in this volume a very touching portrait of the conditions of Black farm workers after Radical Reconstruction under conditions of debt slavery.

- Racism, Revolution, Reaction 1861-1877 – The Rise and Fall of Radical Reconstruction by Peter Camejo

- Thaddeus Stevens: Civil War Revolutionary, Fighter for Social Justice by Bruce Levine

Thaddeus Stevens was among the first to see the Civil War as an opportunity for a second American revolution—a chance to remake the country as a true multiracial democracy. One of the foremost abolitionists in Congress in the years leading up to the war, he was a leader of the young Republican Party’s radical wing, fighting for anti-slavery and anti-racist policies long before party colleagues like Abraham Lincoln endorsed them. It was he, for instance, who urged Lincoln early on to free those enslaved throughout the US and to welcome Black men into the Union’s armies.

During the Reconstruction era following the Civil War, Stevens demanded equal civil and political rights for Black Americans, rights eventually embodied in the 14th and 15th amendments. But while Stevens in many ways pushed his party—and America—towards equality, he also championed ideas too radical for his fellow Congressmen ever to support, such as confiscating large slaveholders’ estates and dividing the land among those who had been enslaved.

In Thaddeus Stevens: Civil War Revolutionary, acclaimed historian Bruce Levine has written the definitive biography of one of the most visionary statesmen of the 19th century and a forgotten champion for racial justice in America.

- Reconstruction – America’s Unfinished Revolution 1863-1877by Eric Foner

Eric Foner’s “masterful treatment of one of the most complex periods of American history” (New Republic) redefined how the post-Civil War period was viewed.

Reconstruction chronicles the way in which Americans—Black and white—responded to the unprecedented changes unleashed by the war and the end of slavery. It addresses the ways in which the emancipated slaves’ quest for economic autonomy and equal citizenship shaped the political agenda of Reconstruction; the remodeling of Southern society and the place of planters, merchants, and small farmers within it; the evolution of racial attitudes and patterns of race relations; and the emergence of a national state possessing vastly expanded authority and committed, for a time, to the principle of equal rights for all Americans.

This “smart book of enormous strengths” (Boston Globe) remains the standard work on the wrenching post-Civil War period—an era whose legacy still reverberates in the United States today.

Categories: Black Struggle, US History

1 reply »